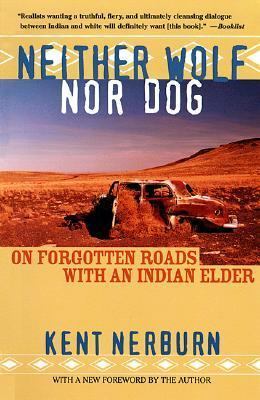

“Neither Wolf Nor Dog” by Kent Nerburn

Neither Wolf nor Dog is another one of those, “I probably wouldn’t have read it on my own and only did because of book group and I’m glad I did” books.

Nerburn, a Minnesota writer with a wife and kid, is summoned peremptorily to a distant Native American reservation where an old Lakota man asks him to help write a book. This is that book. It could have been a cringe-worthy cliche of a white-man telling a Native’s story. And since that’s what it is, it always has that obstacle to overcome. As much as it can, it does.

To do that, Nerburn narrates the whole of things–not only the sermons and talks Dan delivers, but the behavior of the hound who travels with them, plus commentary from Dan’s friend Grover when they go on “a little trip” across country. Nerburn also includes an often unflattering narrative of his own comments and thoughts on the trip, as well as his constant desire to transcend the problem of a person of privilege narrating a person of poverty’s story.

Think of that Thoreau fellow. I’ve read some of his books. He went out and lived in a shack and looked at a pond. Now he’s one of your heroes. If I go out and live in a shack and look at a pond, pretty soon I’ll have so many damn social workers beating on my door that I won’t be able to sleep.

They’ll start scribbling in some damn notebook: ‘No initiative. No self-esteem.’ They’ll write reports, get grants, start some government program with a bunch of forms. Say it’s to help us.

That’s what happened with allotment. They said they were trying to help us. They cut up our reservations into chunks and told us we had to be farmers. When we didn’t farm, they said we were lazy. I don’t remember anything about Thoreau being a farmer. He mostly talked about how great it was to do nothing, then he went and ate dinner at his friend’s house. He didn’t want to farm and he’s a hero. We don’t want to farm and we’re lazy. Send us to a social worker…

White people don’t know what they want. They want these big houses and all kinds of things, they they want to be close to the earth, too. They get cabins, they go hunting, they go camping, they say it makes them close to the earth. But they really think it’s okay only because they have all these other things. We Indians, we lie in cabins and hunt, but it’s not okay because we don’t turn around and go back to big houses and big jobs. We don’t need two lives like white people. The only reason that Thoreau fellow is a hero is because he lived two lives, otherwise he just would have been a bum. They would have sent social workers to his house…

For white people there are only two types of Indians. Drunken bums and noble Indians…

The ones who see us all as wise men don’t care about Indians at all. They just care about the idea of Indians. It’s just another way of stealing our humanity and making us into a fantasy that fits the need of white people.

You want to know how to be like Indians? Live close to the earth. Get rid of some of your things. Help each other. Talk to the Creator. Be quiet more. Listen to the earth instead of building things on it all the time.

Don’t blame other people for your troubles and don’t try to make people into something they’re not. (183-5)

I loved spending time with these people. I often wanted to tell Nerburn to shut up and listen, which is what Dan said to him often. Reading this book made me want to shut up and listen. It made me aware of and uncomfortable in my white privilege. It’s one of a string of non-fiction memoir-y books I’m reading now, not a deliberate choice, but one whose surfacing in my life at this point is probably not random.