“The Testament of Mary” by Colm Toibin

Super short, super cranky but impressive, daring, and with beautiful, evocative prose, I wanted to like it more than I did, though, and had some lingering troubles. In The Testament of Mary, Toibin takes an intriguing idea and gives voice to Mary the mother of Jesus, so often portrayed as demure and all loving. Toibin dares to make Mary bitter and mean. She says the death of her son was not worth whatever it is that the men who pester her say it is.

They appear more often now, both of them, and on every visit they seem more impatient with me and with the world. There is something hungry and rough in them, a brutality boiling in their blood, which I have seen before and can smell as an animal that is being hunted can smell. But I am not being hunted now. Not anymore. I am being cared for, and questioned softly, and watched. They think that I do not know the elaborate nature of their desires. But nothing escapes me now except sleep.

Toibin dares a lot: he portrays Jesus as kind of a show-off-y jerk who wouldn’t listen to others, and shows Mary running from the cross for fear of her life.

A review I read at The American took especial issue with that last:

What troubles me about his Mary is that she is a coward. After her son is nailed to the cross–a scene described in agonizing detail–Mary runs away. She runs away because she cannot help him, because she is afraid and (here is the hardest part to swallow) because she wants to save her own skin.

ToÃbÃn sins here against Scripture and tradition, yes, but also against the more universal code of Motherlove–that irresistible compulsion that drives a mother to protect her child at any cost. Motherlove is the deep knowledge that you would stand between a killer and your child and take a bullet in the face, that you would dive in front of a runaway train to shove your child off the track, that you would part with your own heart if your child needed it and that you would do this gladly. The inventions of tradition and bad art have provided us with too many impossible Marys who bear no relation to us. Do we need another? ToÃbÃn denies Mary what makes her most human, sinning at last against the law of verisimilitude, and giving us one more Mary we cannot believe in.

I take issue with the review author’s “we.” I admire Toibin’s choice, I can absolutely buy a mother running away, since she knows her son is dead or dying. She does regret it later.

The ways in which Toibin didn’t carry me all the way were few, but significant. I kept wondering things like where is James, brother of Jesus, or why, if the gospels weren’t written until many years after his death, they’re being shown here as current with his death. Additionally, while I appreciated the complex humanity he granted Mary, a few times I felt her more as a puppet for Toibin’s anger at the church, rather than as a person of her own.

Mary Gordon at The New York Times noted this, about anachronisms, but I felt the same way about the doubts I had as reading, though I think mine nagged a little more:

This is a place where our associations – sandals and piles of coins versus shoes and bills – create doubts that hang in the air, like an annoying buzz. Or like a tiny pimple on an otherwise beautiful face.

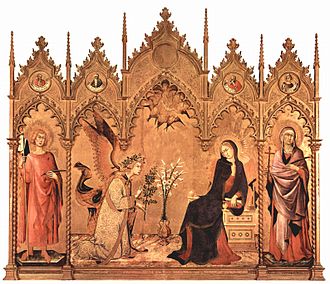

In closing, these are a few images of Mary that have spoken to me over the years, ones that show her as decidedly human.

I love The Annunciation by Simone Martini, because she looks unhappy at the news of the Annunciation:

I love Paolo Veronese’s Holy Family because it shows Mary buttoning up, a motion familiar to those of us who’ve nurses babies, Jesus in a milk coma and clutching his penis. So normal!

I love Madonna and Child by Defendente Ferrari because it shows Jesus nursing, and Mary holding a cloth diaper. This one shows real, messy bodily truths:

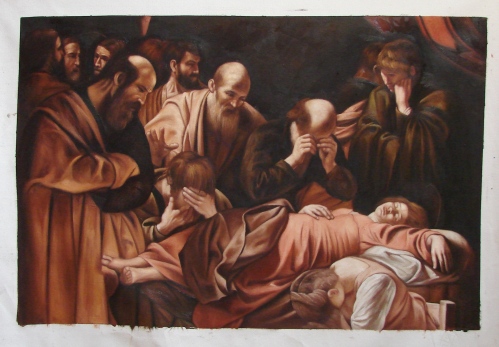

And finally, Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin, which pissed people off because it showed her bloated, old, and with BARE FEET. Also, he used a prostitute, i.e., a real, sexually active woman, as a model.