“Nox” by Anne Carson

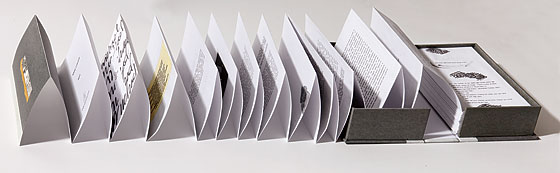

Carson is a professor of Greek, and this “book” is her tribute to her brother, who died after being absent from her life over twenty years. It is not so much a book, but rather a book-shaped object, with a long, folded single sheet of paper inside a cardboard box. The text begins with a poem in Greek, and proceeds to define the words, one at a time, on the left-facing pages, while the right-facing pages contain her memories, photos and letters of her brother. The definitions of the Greek words, or “entries” as Carson at one point emphasizes, seem straightforward at first, but soon it becomes clear that Carson has insinuated herself into them. The sentences used as examples tend to intertwine with the fragments about her brother, and most include a reference to “nox” or “night,” in one meaning. Eventually the poem as a whole is translated, and her memories unfold to include meeting her brother’s widow and attending his funeral.

After finishing, I felt more like I didn’t understand the work than that I didn’t “like” it. I’ve put “like” in quotations, because it’s an unfitting and inadequate word for the response a complicated, ambitious, beautiful work like this deserves. How much richer it must be for Carson to have the scroll this is a copy of as a memoriam to her brother, rather than an urn of ashes. But while I was sometimes moved while I read, or took in, the work, it didn’t stir me deeply as I felt it “should.” This, however, might be a failing in myself, either of understanding, or of empathy. I have not experienced anything near the loss and sorrow described here, and as one reviewer quoted Iris Murdoch as writing, “The bereaved cannot speak to the unbereaved.” I felt similarly distanced during my reading of Joan Didion’s Year of Magical Thinking. Whether it’s a want of feeling in me, or an intellectual distancing by these women, I can’t say.